|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Meteor Falls and Other Natural Phenomena

Between 1392-1863

As Recorded in the Annals of the Chos˘n Dynasty (Korea)*

College of Humanities

Seoul National University

* Expanded from: Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy 69: 199-220, 1998; Dynamics of Comet and Asteroid and Their Role in the Earth History, ed. by Yabushita Shin and Henrard, 1998. Kluwer Academic Publishers. Printed in the Netherlands.

1. Introduction

During the 17th century, there was a long-term drop in overall global temperatures, which led to a sharp reduction in agricultural production. This, in turn, brought about widespread famine and epidemics and had major social and political repercussions. The extended abnormal temperature drop of this period has been recognized by natural scientists, who have called this the "Little Ice Age." However, little research has been done on the cause or causes of this temperature drop beyond John A. Eddy's work on the decline in sunspot activity. After I came across the 17th-Century Crisis theory in the works of Western scholars, I felt that the Annals of the Chos˘n Dynasty (Chos˘n wangjo sillok in Korean; hereinafter referred to as the "Annals") could potentially be a valuable source of reliable information for this time period. The scribes who compiled the Annals were faithful and meticulous in recording all natural and unusual (often seen as supernatural) phenomena, in accordance with the distinctive Confucian view of nature. Because of this, I believed that these records could provide much valuable insight into phenomena that attended and perhaps led to the Little Ice Age. After ten years of research, I can demonstrate that my initial expectations were correct.

At first I concentrated on records from the 17th century, but in tracing the frequencies of the various natural phenomena, I had to push the starting point back to the end of the 15th century. I also covered the records for the period immediately after the Little Ice Age for comparative reference, so in the end, I examined records spanning 470 years in the Annals. Based on these records, I have concluded that the Little Ice Age began as early as the end of the 15th century and lasted until the middle of the 18th century. Furthermore, the data suggests that the cause of the Little Ice Age is linked to the abnormally high number of meteors which fell over an extended period of time.

I am still in the midst of processing the massive amount of data obtained from the Annals--some 25,000 separate records. Therefore, I ask the reader to excuse the fact that I am presenting a work which is not entirely complete, in the hopes of enhancing my research results and analysis with input from other researchers who are working in different but related areas. I welcome healthy debate as well as constructive criticism and will update this paper as a need to arises. (Last revision: 04/16/99)

2. The Annals of the Chos˘n Dynasty

The Chos˘n Dynasty was founded in 1392 and ended in 1910. Although it was renamed as the Great Han Empire in 1897, the royal line remained the same. The Chos˘n monarch left us with many documents and records, but as the official court records, the Annals are certainly the most representative and the most important. The Annals span 518 years and cover the reigns of 27 monarchs. The entries are recorded by year, month and day and comprise a total of 1,945 volumes divided into 940 books--a massive undertaking indeed. The scribes recorded every kind of natural phenomena and astronomical observations, in according with the Confucian precept that natural phenomena reflected the current status of society. In other words, Confucians interpreted aberrations in nature as a celestial warning that humans were doing something wrong. This was especially relevant for the monarch, who as the head of the state, was ultimately responsible for all human activities. Thus monarchs kept a faithful record of phenomena such as eclipses, unusual movements in the constellations, comets, lightning and thunderstorms in the winter, hail, droughts and other unusual occurrences as a gauge of the problems of their administration and an indication that they should repent. Furthermore, they believed that observing and recording such phenomena were a form of paying respect to the heavens.

Confucianism was the predominant ideology of the Ming and Ching Dynasties in neighboring China as well. But for the following reasons, the official Annals of the Ming and Ching Dynasties fail to match the Chos˘n Annals as a reference source. First, the transition from the Ming (1368-1662) to the Ching Dynasty (1663-1911) at the beginning and the middle of the 17th century was marked by constant warfare, which in itself constituted a 17th-century crisis. Another factor is the fact that the Chos˘n Annals were kept off the public record from the start. This principle ensured independence from the sovereign, and therefore greater impartiality. The Ming and Ching Annals, however, were a matter of public record, and thus more susceptible to the prerogatives of the ruling monarch. Under such conditions, scribes may have been pressured to document natural phenomena with less than absolute objectivity. In Korea, the records were kept in specially designed archives to which not even the monarch had access. Finally, the Chos˘n Dynasty was the longest running dynasty in the world, after the 15th century. When considering the significance of the natural phenomena to the Confucian political system, and the degree of integrity evident in the record-keeping, the Chos˘n Annals are an unsurpassed record of five centuries of natural phenomena. As such, they are an unmatched source of data, an invaluable reference for studies of the Little Ice Age.

Any claims regarding the value of this material would not be complete without a reference to the astronomical observation of the Chos˘n monarchs. By the early 15th century, the nation already boasted advanced observatories and other instruments and facilities, which were maintained throughout the 16th century. Among the most highly developed instruments was an astrolabe which used the horizon to measure the movements of planets, comets, and other moving bodies by minute intervals. These were known to be highly sophisticated and accurate instruments. They were kept in duplicate, one set at the royal court, the other at the Office for Observance of Natural Phenomena, which was responsible for observing all astronomical phenomena and weather. At night, five astronomers would take their turn going to the office for observation, to ensure utmost accuracy. Most of the measurements were taken in Seoul, since such facilities were not installed in the provinces. However, phenomena taking place in the provinces which could be seen by the naked eye were all reported to the king.

The world's first rain gauge was invented in Korea in 1442. By 1444, they were installed in 260 counties throughout the country. Every time it rained, officials recorded what time it rained and how much, which they then reported to the central weather administration. This data was used to predict the coming harvest, as well as to assess taxes on crops. Since the tax rate was affected by natural phenomena, officials were instructed to report everything. In this way, a highly centralized bureaucracy was able to administrate an agrarian-based economy based on the regular collection of astronomical and meteorological data from all over the country.

Of course, the Chos˘n Annals also include observations that now seem ridiculous when measured by the standards of modern science. But we cannot conclude that the Annals were in any way fabricated or unreliable. Furthermore, my research focused only on the years from 1392 to 1863. I did not include the latter sections because the reigns of the two monarchs who ruled after the year 1863 are characterized by exceptional circumstances. Nevertheless, the sheer volume of the records documenting 471 years of 25 monarchs comprise 1,893 volumes--888 books in all. From them, I have found 25,000 references to unusual natural phenomena.

3. Analysis Results: Distribution of the Phenomena by Time Period and Region

In my study, I did not include records of solar eclipses, lunar eclipses, and unusual movements of the planets,1) since they cannot really be considered "abnormal" natural phenomena according to today's modern standards.

Table I shows the distribution of the records of abnormal phenomena I examined, divided roughly into 50-year periods. Looking at Table I shows that the records of unusual phenomena were concentrated from Period 3 to Period 7, or the period from 1501-1750. This 250-year period comprises 63% of the total period examined, yet it accounts for 80% of the recorded phenomena. Therefore, it seems safe to assume that there was a high frequency of abnormal natural phenomena concentrated during this period.2)

TABLE I

Total Number of Occurrences for Each Period

| Period | Corresponding Years | Total Number |

|---|---|---|

| Period 1 | 1392-1450 | 2117 |

| Period 2 | 1451-1500 | 1420 |

| Period 3 | 1501-1550 | 6109 |

| Period 4 | 1551-1600 | 4785 |

| Period 5 | 1601-1650 | 3300 |

| Period 6 | 1651-1700 | 3563 |

| Period 7 | 1701-1750 | 2716 |

| Period 8 | 1751-1800 | 936 |

| Period 9 | 1801-1863 | 724 |

| Total | 25670 |

Of course, there are instances where the records may be suspect due to negligence on the part of the observers. Also, the editors of the Annals would sometimes merely summarize phenomena which were repeated over and over. All in all, though, they were consistent in keeping accurate and faithful records. Out of the entire period covered, there is a higher than average percentage of faulty records from the 10-year period from 1496 to 1506, and the roughly 20-year period from 1568 to 1590. During the earlier period, the reigning monarch was a despot who did not want to hear officials telling him to be penitent as they reported the unnatural phenomena, and so he ordered them not to make such reports at all. For the second period, most of the records of that particular ruler, whose reign began in 1567, were lost during the invasion of Korea by the Japanese warlord Toyotomi Hideyoshi in 1592.

Table II shows how frequently each phenomenon occurred in Seoul and in the provinces. According to this, most of the phenomena which occurred in the sky--meteors, colored vapors in the sky, comets and gaekseong or "guest stars", changes in the sun or moon, halos around the sun and moon, and the appearance of Venus during the daytime--were observed and recorded in Seoul.

TABLE II

Regional Distributions of Disastrous Natural Phenomena Recorded in the Chos˘n Dynasty

| Phenomena | Seoul | Other areas | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Meteors | 3363 | 68 | 3431 |

| Colored vapors | 1018 | 34 | 1052 |

| Strange sounds in the Heavens | 10 | 0 | 10 |

| Comets | 1212 | 2 | 1214 |

| "Guest stars" or New stars | 265 | 0 | 265 |

| Abnormal sun | 82 | 14 | 96 |

| Abnormal moon | 19 | 1 | 20 |

| Halo effect / sun | 4459 | 28 | 4487 |

| Halo effect / moon | 1139 | 3 | 1142 |

| Daytime appearances of Venus | 4882 | 5 | 4887 |

| Thunders, lightning | 1434 | 936 | 2370 |

| Hail | 630 | 1376 | 2006 |

| Frost | 170 | 435 | 605 |

| Unseasonal snow | 68 | 309 | 377 |

| Heavy rain | 129 | 58 | 187 |

| Frightful rainstorms | 303 | 330 | 633 |

| Violent windstorms | 92 | 140 | 232 |

| Heavy snow | 21 | 15 | 36 |

| Colored snow and rain | 43 | 47 | 90 |

| Dust storms (Micrometeorites) | 25 | 4 | 29 |

| Daytime darkness | 46 | 8 | 54 |

| Fog | 621 | 30 | 651 |

| Earthquakes | 216 | 1284 | 1500 |

| Tidal waves | 4 | 108 | 112 |

| Change of water color | 8 | 25 | 33 |

| Unusually low temperature | 40 | 24 | 64 |

| Unusually high temperature | 61 | 26 | 87 |

| Total | 20360 | 53110 | 25670 |

This is because the facilities needed for advanced astrological observation were only available at the Office for Observing Natural Phenomena in Seoul. Most of the reports from the provinces were events that could be easily seen by the naked eye or things that were extraordinarily unusual. As can be seen from the table, a small number of reports on meteor movements, colored vapors in the sky, changes in the sun, and halos around the sun, were also recorded in the provinces. In any case, the fact that most of the observations were made at one location can be a benefit since it helps guarantee the consistency of the records.

4. Analysis Results: Most Common Phenomena between 1500-1750

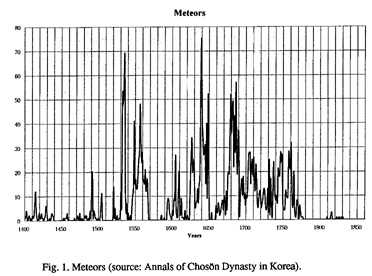

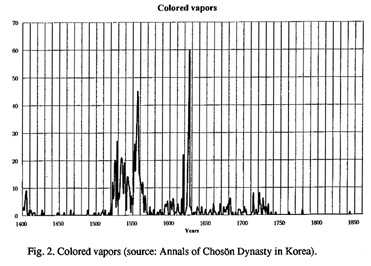

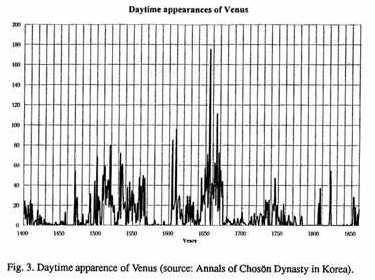

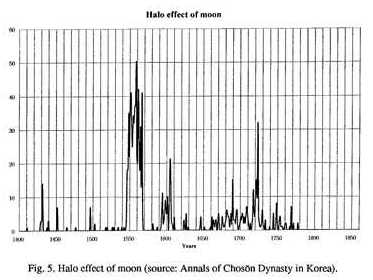

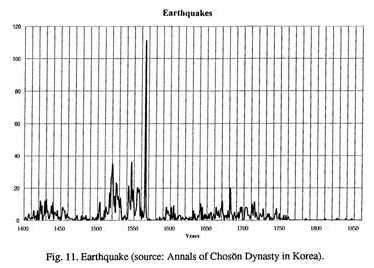

We can analyze the cause of the unusual natural phenomena between 1500-1750 by examining the various types of phenomena which occurred most frequently during this period. As shown in Table III, these include: 1) meteor appearances and fallings; 2) colored vapors in the sky (white vapors, black vapors, red vapors, "fire" vapors, bright lightning flashes); 3) the daytime appearance of Venus; 4) halos around the sun or moon; 5) thunder and lightning; 6) hail; 7) violent windstorms; 8) frost; 9) unseasonal snow; 10) sudden darkness during the day; 11) dust (micrometeorite) storms; 12) fog or fog-like clouds; 13) changes in the sun or moon; 14) colored snow or rain; and 15) earthquakes. While there are also high frequencies of droughts, floods, plagues, and pestilences during this period, these are more the result of natural phenomena rather than phenomena themselves, and so I have excluded them from this examination. As can be seen in Figures 1-11, the fact that the above mentioned phenomena all occurred at an unusually high frequency over the same period suggests that there is a close relationship between them. Below are individual analyses and explanations of each phenomenon.

4. 1. Meteor Appearances And Fallings

Meteors were recorded according to three different names: yuseong, biseong (flying stars) and yongduseong (flame-headed stars). According to astronomy texts of that time, yuseong were meteors which moved downward and from east to west, while biseong moved upward and disappeared in the distance, and yongduseong were meteors which fell during the daytime. The records on the appearances and fallings of these meteors were done in one of the following formats.

For records in B) format, the size and shape were compared to a drinking cup, a bottle, a fist, a pear, a water jar, a small box, a round barrel, and a bowl, while the color was described as red, white or blue. Records in C) format referred to the sound it made when it passed by or the light it gave upon the land. The four different formats of the records were not differentiated according to size; rather, the system for describing details changed according to the times, as evidenced by the trend in the records from Period 6 and Period 7 generally showing a rough sketch. Only meteors which were thought to be usually large or bright were recorded; smaller meteors or shooting stars were not recorded from the very start.

TABLE III

Periodic Distribution of Disastrous Natural Phenomena Recorded in the Chos˘n Dynasty

(See Table I for a definition of periods P1-P9)

| Phenomena | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | P6 | P7 | P8 | P9 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meteors | 103 | 69 | 422 | 387 | 766 | 740 | 695 | 239 | 10 | 3431 |

| Colored vapors | 48 | 9 | 333 | 325 | 211 | 61 | 61 | 3 | 1 | 1052 |

| Strange sounds in the Heavens | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| Comet observations | 21 | 198 | 221 | 102 | 37 | 102 | 84 | 75 | 374 | 1214 |

| Actual comets | 5 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 4 | 8 | 5 | 3 | 14 | 61 |

| "Guest star" or New star observations | 0 | 0 | 0 | 127 | 102 | 0 | 14 | 22 | 0 | 265 |

| Actual "Guest stars" or New stars | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 9 |

| Abnormal sun | 6 | 0 | 16 | 27 | 23 | 9 | 13 | 2 | 0 | 96 |

| Abnormal moon | 0 | 0 | 1 | 10 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 20 |

| Halo effect / sun | 424 | 352 | 1662 | 1378 | 266 | 121 | 239 | 44 | 1 | 4487 |

| Halo effect / moon | 27 | 16 | 145 | 557 | 78 | 116 | 176 | 27 | 0 | 1142 |

| Daytime appearances of Venus | 252 | 339 | 1186 | 397 | 829 | 1141 | 388 | 116 | 239 | 4887 |

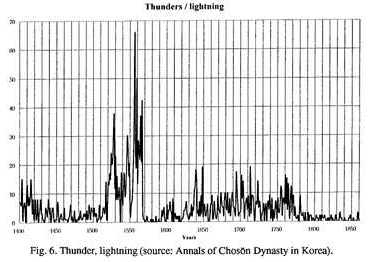

| Thunders, lightning | 264 | 108 | 547 | 456 | 209 | 250 | 282 | 211 | 43 | 2370 |

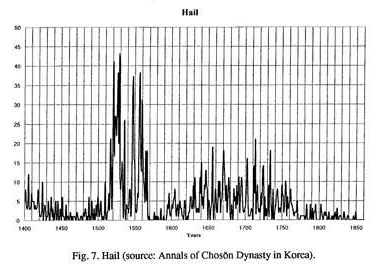

| Hail | 177 | 68 | 578 | 260 | 223 | 295 | 262 | 108 | 35 | 2006 |

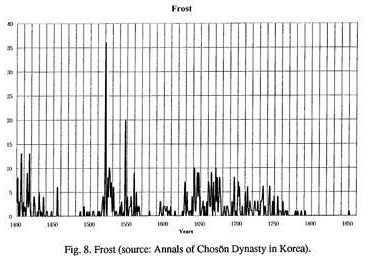

| Frost | 107 | 11 | 145 | 38 | 84 | 121 | 81 | 17 | 1 | 605 |

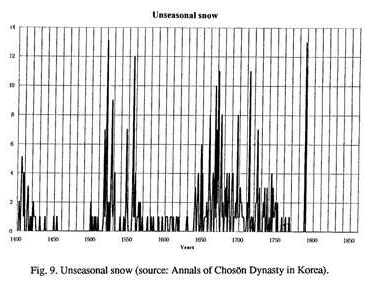

| Unseasonal snow | 37 | 3 | 70 | 32 | 35 | 117 | 65 | 18 | 0 | 337 |

| Heavy rain | 63 | 1 | 38 | 13 | 5 | 22 | 21 | 17 | 7 | 187 |

| Frightful rainstorms | 149 | 112 | 59 | 34 | 134 | 89 | 47 | 7 | 2 | 633 |

| Violent windstorms | 46 | 4 | 61 | 28 | 30 | 42 | 16 | 3 | 2 | 232 |

| Heavy snow | 2 | 7 | 7 | 0 | 2 | 14 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 36 |

| Colored snow and rain | 14 | 8 | 29 | 18 | 8 | 11 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 90 |

| Dust storms (Micrometeorites) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 7 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 29 |

| Daytime darkness | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 14 | 24 | 13 | 2 | 0 | 54 |

| Fog | 144 | 20 | 45 | 280 | 91 | 22 | 48 | 1 | 0 | 651 |

| Earthquakes | 183 | 78 | 482 | 287 | 110 | 185 | 157 | 13 | 5 | 1500 |

| Tidal waves | 4 | 1 | 7 | 5 | 14 | 33 | 38 | 7 | 3 | 112 |

| Change of water color | 14 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 12 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 33 |

| Unusually low temperature | 8 | 1 | 28 | 3 | 11 | 9 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 64 |

| Unusually high temperature | 24 | 15 | 20 | 15 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 87 |

| Total | 2117 | 1420 | 6109 | 4785 | 3300 | 3563 | 2716 | 936 | 724 | 25670 |

If the records on meteors are understood as was described above, then there is a high probability that the large number of meteor appearances from Period 3 to 7 had a large influence on the other phenomena which also occurred during that period. Altogether, about 3,330 relatively large meteors were observed over the 250-year period just in Seoul, which means that the number of meteors which enter the atmosphere throughout the world must have been enormous. If that many meteors fell to the earth concentrated during the designated period, the dust given off as they burned or exploded would have had a considerable effect on the other phenomena.

(click charts for a larger image)

4.2. Colored Vapors In The Sky

Among the recorded phenomena I examined, the one which would appear to be most closely related to meteor fallings would be the colored vapors in the sky. Altogether, there were 1,052 records of colored vapors, which were described in the following manner: paekki ("white vapors"), heukki ("black vapors"), cheokki ("red vapors"), hwagi ("fire vapors"), and cheon-gwang ("bright lightning flashes"). Of the 1,052 records, 94% or 991 records occurred from Periods 3 through 7.

On March 24, 1933, a meteor fell from the sky at Pasamonte, New Mexico, in the United States. Dr. H. H. Nininger has done a well-known study of this event. What interested me most from the Pasamonte research were the pictures of the site of the meteor falling. Charles M. Brown, who was directly under the object's line of fall, captured a wonderful picture of--(a) "the fireball" and 15 minutes after that photo, C. R. West, 160 miles to the north in Timpas, Colorado, snapped (b) the "luminous dust cloud of the Pasamonte meteorite." (see figure 12) Picture (a) is an almost exact representation of one of the records of meteor sightings commonly found in the Annals--"Its shape was like a pear and its color was white, while its tail was a certain length." The white and black cloud shown in picture (b) can be well described by the countless records of "white cloud-like vapors," "black cloud-like vapors," "silk- (or cotton) lined white vapor," "white vapors," or "black vapors" found in the Annals. This picture was taken around 5:20 a.m. and the dust was too low for the luminosity to be affected by sunlight. There are many incidents recorded in the Annals of these white or black vapors appearing at night. Taking all of this into consideration, of the records of colored vapors found in the Annals, the records of white and black vapors can be interpreted as being signs of a meteor passage. This means that these recorded incidents should be added to the total number of meteors observed to have entered the earth's atmosphere.

Figure 12

From Out of the Sky, by H.H. Nininger (1952)

Also included in the colored vapor category are the records of the red vapors, the fire flashes, and the bright lightning flashes. It seems more than likely that the fire vapors and the bright lightning flashes are similar or related to the luminosity seen at Pasamonte. The red vapors are generally considered to be observations of the aurora borealis, but the number of red vapors recorded is too high for all of them to be considered auroras. As is well-known, on June 30, 1908, at 7:15 a.m. (local time), a small asteroid struck the earth at Stony Tunguska River in Siberia. It is said that the "fire in the sky" was so bright that people were able to play cricket and read newspapers by the resultant light some 5,000 kilometers away in England, and that in Belgium a huge red flame was seen over the horizon after the event. Based on this, many of the red vapors, fire flashes and lightning flashes recorded in the Annals can be interpreted as being phenomena witnessed near the site of meteor collisions.

4.3. Daytime Appearance of Venus

There are 4,887 instances of Venus appearing during the daytime recorded in the Annals. Of these, 3,941 or 87% of them took place during Periods 3 through 7. Records on this phenomena can be divided into the following four formats:

Records in A) format appear in all the Periods, but are particularly numerous in Periods 1, 2, 8, and 9. On the other hand, records in the B), C), D) formats are mostly found between Period 3 through 7. Most of the appearances occurred between 11 a.m.-1 p.m. or 1-3 p.m., with the location being southeast, due south, or southwest. Records in format D) were records in C) format of Venus appearing due south, cautioning that it appeared brightly. In Eastern astrology, Venus is the representation of yin in the yin-yang philosophy. In other words, it is the direct counterpart of the sun, the representation of yang. Under this system of belief, the appearance of Venus during the daytime constitutes a warning. The reason given for this phenomenon was that the light and heat of the sun generally became weaker. As is explained later, in Periods 3 through 7, there are countless reports of dust falling from the sky and darkness covering the ground in all directions like fog and also the sun losing light. These phenomena are the result of the dust caused by the large number of meteors which entered the atmosphere and burned or exploded concentrated over an extended period of time. The reason that Venus appeared so often during the daytime is quite possibly that the rays of the sun were partially blocked by meteor dust in the atmosphere, thereby weakening the sunlight.

4.4. Halos Around the Sun and the Moon

Halos around the sun and the moon appeared at a similar frequency to the daytime appearance of Venus. Out of a total 5,629 recorded instances (4,487 solar halos, 1,142 lunar halos), 4,739 or 84% were sighted in Periods 3 through 7. Most of the records were in the following formats:

Most of the records on halos found in Periods 1, 2, 8, and 9 were of the simpler A) and B) formats, particularly format A). In contrast, the majority of the records from Periods 3 through 7 were the more complex B), C) and D) formats. The sun was the symbol of the king, the source of all creation, and any unusual changes in its appearance could not help but attract special interest. The more complex the changes, the more shocking this phenomenon was.

Simple halos such as those described in format A) occur when there is a lot of moisture in the atmosphere, so they cannot be considered as a problem. However, more complex halos such as those described in formats B), C), and D) cannot be seen so easily are phenomena which are related to the irregular conditions in the earth's atmosphere during that period. In other words, it appears that atmospheric anomalies such as the presence of so much meteor dust led to the formation of these strange halos.

4.5. Thunder And Lightning and Hail

Altogether there were 2,370 records of thunder and lightning, 74% of which, or 1,746 cases, took place during Periods 3 through 7. Records of hail storms amounted to 2,006 incidents, with 81% or 1,622 happening during the crucial Periods 3-7.

The natural climatic conditions of Korea are such that thunder and lightning usually occur during the summer months. Looking at Table IV shows that during Periods 3 through 7, thunder and lightning were spread out over every month and concentrated from the eighth month to the twelfth month (by the lunar calendar) of the year. In fact, the summer months--the 4th, 5th, and 6th lunar months--had comparatively low totals. It is safe to say that these occurrences were unrelated to seasonal patterns. On the other hand, the records of hail are concentrated in the 4th, 5th, and 6th lunar months. The fact that thunder and lightning and hail occurred so frequently out of season means that the underlying reasons for these phenomena were not seasonal-related.

There were many records of thunder/lightning and hail occurring simultaneously; in other words, oftentimes hail mixed with rain would be falling as thunder and lightning struck. The hailstones were variously described as being the size of bird's egg, a hazelnut, a chicken egg, a duck egg, a small pot, a small box, and a round barrel. When larger-size hailstones fell, not only were crops destroyed, but there were many instances where animals and even people were killed by the falling hailstones. The frequent occurrences of hail storms mixed with thunder and lightning during a time when many meteors were appearing and falling brings to mind the "impact winter" or "cosmic winter" predicted in the great asteroid-collision theory propounded by Luis Alvarez and others.

4.6. Violent Windstorms, Frost, and Unseasonal Snow

According to the Alvarez team's theory, an asteroid with a diameter of 10km struck the earth some 65 million years ago. If it hit the earth, it would inject a huge cloud of dust up through the stratosphere, which would block sunlight. Hail and snow would fall continously, and the earth would be covered in darkness and cold for several years. If it landed in the ocean, it would send great amounts of water vapor and steam into the air, which would temporarily produce a greenhouse effect and cause temperatures to rise. Shortly after, this vapor would turn into rain and fall to the earth's surface and the dust particles in the upper atmosphere would initiate global cooling.

Of course, the meteors which fell in such concentration between c.1500-1750 are not comparable in size to the huge meteorite thought to have struck the earth 65 million years ago. However, a larger than normal number of smaller meteors falling to earth over a long period of time could conceivably produce a scenario similar to that caused by the Alvarez meteor, at least in terms of nature if not in size.

TABLE IV

Monthly Distribution of Disastrous Natural Phenomena during 1501-1750 Recorded in the Chos˘n Dynasty Annals

(Lunar calendar)

| Phenomena | mon 1 | mon 2 | mon 3 | mon 4 | mon 5 | mon 6 | mon 7 | mon 8 | mon 9 | mon 10 | mon 11 | mon 12 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meteors | 183 | 180 | 184 | 185 | 111 | 229 | 305 | 309 | 475 | 388 | 242 | 219 | 3103 |

| Colored vapors | 139 | 151 | 141 | 71 | 66 | 63 | 38 | 41 | 37 | 77 | 72 | 95 | 991 |

| Strange sounds in the Heavens | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| Comets | 38 | 55 | 5 | 22 | 9 | 26 | 101 | 37 | 46 | 87 | 65 | 55 | 546 |

| "Guest stars" or New stars | 39 | 15 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 11 | 41 | 13 | 68 | 46 | 243 |

| Abnormal sun | 6 | 13 | 19 | 16 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 11 | 3 | 7 | 7 | 88 |

| Abnormal moon | 3 | 1 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 18 |

| Halo effect / sun | 493 | 495 | 488 | 409 | 308 | 162 | 179 | 231 | 193 | 193 | 215 | 300 | 3666 |

| Halo effect / moon | 144 | 133 | 108 | 88 | 47 | 31 | 54 | 80 | 87 | 90 | 105 | 105 | 1072 |

| Daytime appearances of Venus | 531 | 261 | 158 | 173 | 184 | 276 | 438 | 408 | 408 | 362 | 359 | 383 | 3941 |

| Thunders, lightning | 73 | 28 | 13 | 41 | 40 | 55 | 24 | 150 | 492 | 479 | 222 | 127 | 1744 |

| Hail | 8 | 43 | 117 | 388 | 333 | 106 | 71 | 142 | 211 | 144 | 47 | 8 | 1618 |

| Frost | 0 | 2 | 55 | 183 | 93 | 22 | 14 | 76 | 22 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 469 |

| Unseasonal snow | 0 | 0 | 107 | 94 | 29 | 8 | 6 | 24 | 43 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 319 |

| Frightful rainstorms | 7 | 9 | 12 | 20 | 37 | 52 | 70 | 84 | 38 | 14 | 12 | 8 | 363 |

| Violent windstorms | 9 | 6 | 8 | 31 | 18 | 15 | 30 | 29 | 19 | 7 | 2 | 3 | 177 |

| Heavy rain | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 9 | 19 | 25 | 14 | 10 | 4 | 9 | 1 | 99 |

| Heavy snow | 1 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 13 | 27 |

| Colored snow and rain | 8 | 12 | 22 | 16 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 67 |

| Dust storms (Micrometeorites) | 1 | 1 | 11 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 29 |

| Daytime darkness | 0 | 6 | 18 | 12 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 52 |

| Fog | 34 | 23 | 32 | 25 | 17 | 21 | 17 | 17 | 23 | 64 | 119 | 94 | 486 |

| Earthquakes | 120 | 95 | 102 | 96 | 93 | 79 | 46 | 97 | 112 | 104 | 129 | 148 | 1221 |

| Tidal waves | 0 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 13 | 13 | 23 | 18 | 6 | 5 | 7 | 3 | 97 |

| Change of water color | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 19 |

| Unusually low temperature | 3 | 1 | 5 | 11 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 55 |

| Unusually high temperature | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 11 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 46 |

| Total | 1841 | 1542 | 1621 | 1921 | 1430 | 1189 | 1459 | 1786 | 2289 | 2065 | 1706 | 1633 | 20473 |

There are many instances recorded in the Annals of violent windstorms occurring with thunder and lightning mixed with hail or rain during this period. The monthly distribution of the storms recorded during this period indicates that these were not ordinary seasonal typhoons. Even if they were not accompanied by thunder, lightning, or hail, many of these storms were unimaginably strong.

An observer from Cholla-do reports, "The head regent of Yosan-ku said that on the 13th day of the 6th month, between 3-5 p.m., a white dragon appeared in the middle of clear skies, whose wriggling form was clearly visible. A little while later, a fog cloud covered the land everywhere which was so thick that one could not discern things even at close range. A severe rainstorm stirred up, with heavy thunder and lightning. Official Min Chung-il's house in the town was destroyed by the storm and the things inside were sent flying in air landing no one knows where. A three-year-old girl also disappeared and could not be found after much searching. His 80-year-old father and wife were both struck by lightning. They are in comas, and will die any moment." This is a unusual natural phenomenon. (Annals 25-084a, 06 29, 1605)

The numerous records of frost and unseasonal snow which also occurred during this period help attest to the overall temperature drop related to the meteor fallings. As can be seen in Table IV, unseasonal snow fell frequently, not only in the 3rd, 4th and 9th lunar months, but even during the 5th, 6th, 7th, and 8th lunar months.

4.7. Darkness, Dust (micrometeorite) Storms, Fog and Fog-like Clouds, Changes in the Sun or Moon, and Colored Snow or Rain

Table III shows that there were many instances recorded where dust fell almost unendingly, or the land became dark everywhere, or a "fog-like element" covered the land. Related to these are the phenomena where the sun or the moon lose their light and turn red or dark, or where there appear to be two or three suns or the sun is shaking. The report on the weather situation in Seoul from the 12th day of the 3rd lunar month to the 24th day of the 4th lunar month in 1661 give a gook account of the irregular climatic conditions.

Seoul, 1661:

Since it has been confirmed that a large number of meteor appeared and fell during this period, it is not that hard to figure out the reasons for these phenomena. The dust resulting from a meteor falling would have accumulated, covering the area like a fog, even to the point of approaching darkness. The light of the sun and the moon would have been blocked by this layer of dust, which would have caused them to appear red. The sun appearing in double or triple, or the sun shaking are also both phenomena which would have been caused by the refraction of the sun's rays by dust. The black rain, "grass-seed" rain, the "grain-seed" rain or "pineflower dust" rain, or the red/yellow/black snow described in the records would have been caused by the meteor dust being mixed with the rain or snow.

TABLE V

Reports on the Meteor Falling at around 7 P.M. on the third Lunar Month of 1533 in Kangwon-do Province.

| Area | Position relative to impact site | Phenomenon and time | Location of appearance | Tail length | Meteor appearance and color | Special details about its motion | Earthquake, thunder |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kumsong | impact site | Meteor and earthquake around 7 P.M. | In middle of sky from south to north | flame | after fall, earthquake, thunder sound | ||

| Kimhwa | 28 km SSW | Meteor | from southwest to northwest | small vase-like fire | Spinning, became dark all around | explosion sound like thunder | |

| Cholwon | 40 km SW | Meteor | 2 chok (0.6m) | jar | Firecracker-like noises while flying | Thunder sound | |

| Pyonggang | 25 km W | Meteor | In middle of sky from west to east | flame | |||

| Ichon | 60 km NW | Meteor | In the southeast from south to north | fireball | Thunder sound, (from east to west) | ||

| Hapgok | 72 km NNE | Earthquake | from south to west | Earthquake | |||

| Seoul | 110 km SSW | Meteor, evening | from below the Polestar fortress to the northern sky | 8-9 chok (2.4-2.7m) | water jar-like flame, red | gave light to the land, slowly spinning |

4.8. Earthquakes

An extremely large number of earthquakes took place during Periods 3-7. Of the total 1,500 recorded instances, 1,225 or 81% took place during this critical period. This means that over the 250-year period, an average of six earthquakes took place every year. Nowadays, earthquakes occur so infrequently in Korea that it is considered to be an earthquake-safe area by modern standards. Given Korea's geological situation, it is hard to believe that there were so many earthquakes recorded during this period, particularly since there were no recording instruments. However there seems to be no reason to question the records themselves. Looking carefully at the records, the observers used different terms according to the severity of the shaking and also differentiated between country-wide and regional earthquakes, which would lead us to believe in the faithfulness of their recording. In one town in the northern part of the Korean peninsula, an "earthquake swarm" is recorded to have taken place from the 6th day of the 9th month of 1565 to the 26th day of the Ist month of 1566, with total 99 earthquakes taking place during the four-month-plus period. It would be difficult to explain such frequent repetition of earthquakes simply through the movement of the earth's tectonic plates.

At the time of the previously mentioned 1908 Siberia meteorite collision, a strong tremor was measured on earthquake sensors in the city of Irkuts, located along the shores of Lake Baikal. Researchers on comets and meteoroids say that if a fireball such as a comet or meteor impacts, the intense heat puts tremendous pressure on the ground and compresses the surrounding area. A shock wave is created which then becomes a seismic wave which travels aroun the globe. Table V is based on the reports from the towns closest to a site in Kangwon-do province where a meteor fell between 7-9 p.m. on the 9th day of the 3rd month of 1533. Related to this, two areas about 72km north-northeast of the impact site reported experiencing earthquakes, and the towns within 40 km reported hearing a violent, thunder-like explosion. Judging from this, many of the records of earthquakes and thunder found in the Annals are not ordinary earthquakes and thunder, but rather the shock waves and explosion sounds caused by meteor fallings being mistaken as such. The fact that the observers used phrases like "a violent thunder-like explosion occured" instead of the more formal "thunder occured" demonstrates that the observers felt a slight, but noticeable differences in what they experienced.

4.9. Fires

Among the records of meteor falling, there are many quotes and comments that fires burst out when they hit. The people of that time differentiated such fires from other fires caused by lightning by calling them "heaven-sent fires." There is record (Sept./09/1503) from a region in Pyong-an-do Province that in 1503 a private household's grain supply was burned by "heaven-sent fire," although there was also a note that after that event, grain grew better on the land, which had been recently reclaimed from the sea, and so the people were happy. Four years later, a record frequent appearances of flame-like red vapor in the sky, fire broke out on a far-away high mountain, burning several acres, which many said was related (Jan./12/1507). From a branch office in Koseong in Kyongsang-do Province, there is a report that on the third day of the seventh month of 1538, a dark cloud covered the skies and thunder and lightning appeared. Suddenly, rain started falling and the skies darkened; then heaven-sent fire fell and burned a pine grove. (Chonsonwanjo sillok 18-191) And there is another report from Chongju in Pyongan-do Province that on Sept/16/1602, some instruments and objects made out of grass which were piled up a private house caught afire and burned up, even though it was raining (CWS 24-422).

For a long time, no formal measures were taken to help those who suffered damage from fires caused by meteor collisions. However, as such instances and damage increased, the government initiated emergency relief measures for such victims beginning in 1660, which is detailed in Table VI.

TABLE VI

Emergency Relief Measures for Victims of Unnatural Fires in the 17th and Early 18th Centuries

| Date | Location (Province) | Extent of Damage | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1/20/1668 | Chongsong (Kyongsang-do) | 50 commoners' houses | Violent windstorm |

| 2/05/1668 | Seoul and Nearby Areas | Daily fires | |

| 3/14/1668 | Haeju (Hwangjae), Seoul | ||

| 6/29/1676 | Kyonggi-do | Royal tomb ritual altars | |

| 3/07/1680 | T'ongchon + 4 towns (Kangwon-do) | 536 households | Violent winds and mountain fires |

| 3/14/1682 | Pyongyang (Pyongan-do) | 344 households | |

| 8/25/1683 | Chongju (Pyongan-do) | Crops | Thunder/lightning |

| 2/27/1684 | Kanghwa-do Island (Kyonggi-do) | Extremely severe damage | |

| 3/08/1684 | Pyonghae (Kyongsang-do) | ||

| 5/11/1685 | Pyongyang (Pyongan-do) | 1,000households | |

| 3/04/1686 | Chonju (Cholla-do) Pyonghae (Kyongsang-do) | Commoners' houses | |

| 2/10/1687 | Chongson (Kangwon-do) | ||

| 4/10/1688 | Koch'ang (Cholla-do) | ||

| 4/10/1690 | Kaeryong (Kyongsang-do) | 300 households | 3 or more deaths |

| 6/11/1690 | Nak'an (Cholla-do) | 150 households | |

| 10/03/1690 | Nak'an (Cholla-do) | 200 households | |

| 2/14/1691 | Nangch'on (Kangwon-do) | Commoners' houses | 7 deaths |

| 5/20/1692 | Okgu (Cholla-do) | About 60 households | |

| 4/23/1710 | Kansong +3 towns (Kangwon-do) | Rows of houses destroyed in large fire |

The type of fires described in Table VI were not human-caused fires but unpreventable fires caused by natural phenomena, which is why the government decided to target measures for these victims. While there are no detailed descriptions of the actual circumstances, it is safe to assume that many were related to meteor impacts since they were accompanied by thunder, lightning and violent gales.

5. Conclusion

The findings of my analysis of the records found in the Chos˘n Annals on unusual natural phenomena between 1500-1750 can be summarized as follows:

Reference Notes

1) The Korean term seongbyon used to describe when planets would switch places in the course of their movements, which was thought to be abnormal. The Chos˘n observers figured out what was happening by the middle of the 15th century and discontinued recording such observations at the time, but as more and more strange phenomena were witnessed in the skies during the 16th century, they began to observe and record these events once again. Yi Taejin, 1996, p. 96.

2) Some may question whether the wide gap in the frequencies of these periods and the other periods could be due to the failings or lack of consistency of the observers. However, Periods 2 and 8 were among the most politically stable and economically prosperous times in the 500 years of the Chos˘n Dynasty, and the records in the Annals for those periods are considered to be among the most accurate and meticulous, which should dispel such doubts. In fact, it would be accurate to view the political stability and economic development of these period as having stemmed from the reduction in natural disasters.